Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

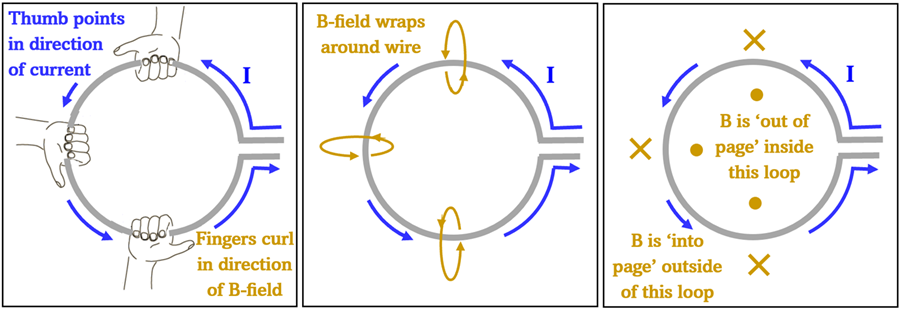

In the previous section of this lesson, we explored how a long, straight current-carrying wire produces a magnetic field around the wire. This magnetic field forms a circular loop that can be described using the “Field-finding” Right Hand Rule.

What if, however, instead of using a straight current-carrying wire, we curved the current-carrying wire into a loop? How could we describe the magnetic field for this situation?

If you zoom in enough on a loop of wire, we can think of the loop of wire as merely a collection almost straight segments of wire that create their own magnetic field around that segment of wire according to the “Field-finding” Right Hand Rule.

The "Field-finding" Right Hand Rule can be used on any segment of wire to show that hte magnetic field wraps around that segment of wire and points into the page anywhere outside of the loop and out of the page anywhere inside the loop of wire.

There is something very important to observe here. Notice that inside the loop of wire all the contributions to the magnetic field from each wire segment are pointing in the SAME direction—out of the page. In other words, by merely bending a wire into a loop and passing current through it, we’ve magnified the strength of the magnetic field inside the wire loop. This is because the magnetic field from each wire segment around the loop overlaps with each other. It is still true that the current creates a magnetic field that surrounds the wire--but inside the loop these add together to magnify the magnetic field.

The Magnetic Field Inside a Solenoid

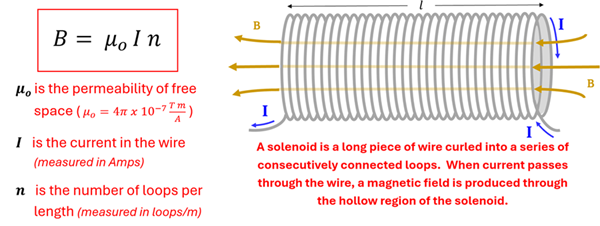

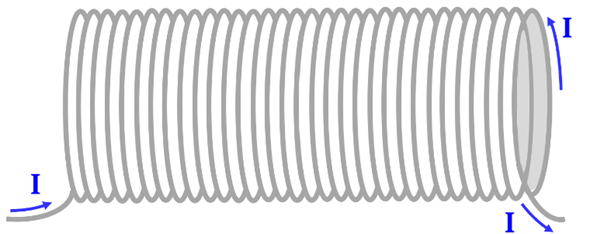

As a clever physics student, you might ask the question, “What would happen if I put many loops of a current-carrying wire side by side?” as shown in the figure below. If your intuition is that the magnetic field down the center of the loops would be even stronger still, you’d be right! A solenoid is simply a coil of wire wrapped in a series of consecutively connected loops. For a very long solenoid that carries current, the magnetic field strength through the center of the solenoid can be calculated using the equation below.

B = µoIn. where B is the magnetic field strength, µo is the permeability of free space, I is the current in the wires (measured in Amps), n is the number of loops per length (measured in loops/m). A solenoid is a long piece of wire curled into a series of consecutively connected loops. When current passes through the wire, a magnetic field is produced through the hollow region of the solenoid.

The number of loops per length, n, is simply calculated by taking the number of loops (N) and dividing it by the length (l) of the solenoid.

In the next section of this lesson, we’ll use Ampere’s Law to derive this expression. There we will see that this relatively simple expression assumes that the length of the solenoid is much greater than the radius of the solenoid—that is why we will continue to refer to a very long solenoid. In this lesson, however, we’ll simply use this result to determine how we could use a solenoid to design the strongest magnetic field possible.

Examples

Example 1

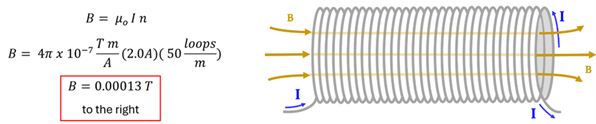

Problem: Determine the magnitude and direction of the magnetic field inside a long, hollow solenoid making 50 loops/m and carrying 2.0 A of current.

Solution: To find the direction of the magnetic field inside the solenoid, we can apply our “Field-finding” Right Hand Rule to any small segment of wire around a single loop. You might consider a small segment of wire on the last loop to the far right, for example. Regardless of the small segment you select, we will see that the magnetic field inside the core of the solenoid points to the right. Then, using the equation for the magnetic field inside a solenoid, we can substitute values and calculate the magnitude of the magnetic field.

Example 2

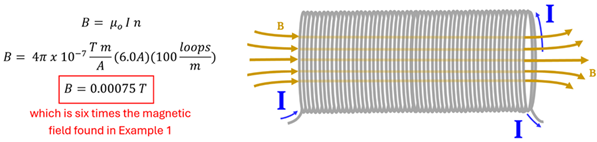

Problem: As a design engineer, you are given the task to modify the solenoid given in Example 1 so that it creates a magnetic field that is six times larger through its core (the hollow region inside the solenoid). What might you do to accomplish this task?

Solution: : Since the equation for the magnetic field inside the core of a solenoid depends on three variables that are multiplied together, we could increase any of these quantities so that their product is six times larger. Consider, for example, if we tripled the current to 6.0 A and doubled the number of loops per length to 100 loops/m. Now our calculations would give us a magnetic field six times that of the magnetic field given in Example 1.

You might get the sense that you could continue to increase the current and number of loops per length to create a stronger and stronger magnetic field. That is true. Engineers find that there are limits to this, however. As the number of loops per length increases you will need to use thinner wire. Thinner wire offers more electrical resistance which in turn decreases the current that can flow through the wire. So, while in theory this works, in practice there are limits to the strength of the magnetic field that we can create.

There is one other term in our equation, however, that we have treated as a constant—the permeability of free space, µo. This is indeed a constant if the core region of the solenoid is hollow. What if, however, you wrapped the wire around something other than empty space? Is it possible to create an even stronger magnetic field simply by putting a certain material inside the core region of the solenoid? If you are asking these questions, you are well on your way to designing the strongest magnet yet! This leads us to what we’ll explore next--the electromagnet.

The Electromagnet

Given all we’ve investigated so far, we are ready to explore how some of the world’s strongest magnets are made. The world’s strongest magnets are not found in rocks (such as magnetite) that we dig up from the ground. They are not found in nature at all. The strongest magnets are solenoid with the core filled with a ferromagnetic material. The strongest magnets are electromagnets.

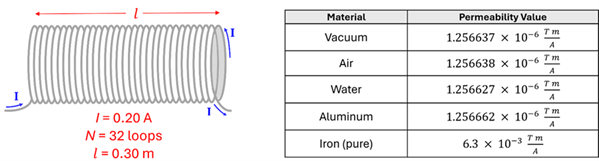

In Examples 1 and 2 above, we assumed that nothing but empty space (or maybe air) filled the core region of our solenoid. In the previous section of this lesson, however, we alluded to the fact that the permeability of free space, µo, gets replaced by the permeability, µ, in all our magnetic field equations if the material between the current carrying wire and the place where we want to find the magnetic field is filled with something other than empty space. A table of permeabilities shows us that many substances—such as air, water, and aluminum—have approximately the same permeability value as ‘free space’ (i.e. a vacuum). The table also show us a material—namely pure iron—that has a permeability value that is thousands of times larger.

| Material |

Permeability Value |

| Vacuum |

1.256637 x 10-6 Tm/A |

| Air |

1.256638 x 10-6 Tm/A |

| Water |

1.256627 x 10-6 Tm/A |

| Aluminum |

1.256662 x 10-6 Tm/A |

| Iron (pure) |

6.3 x 10-3 Tm/A |

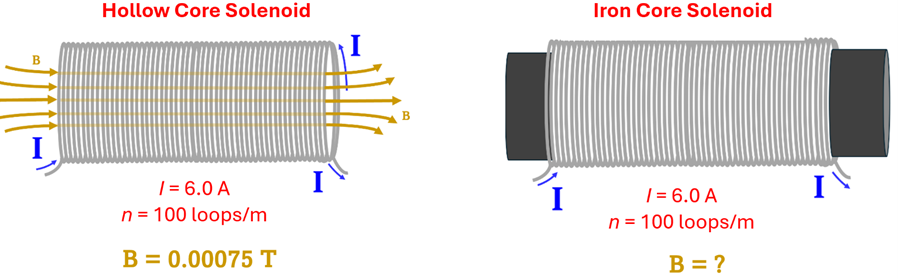

Filling the core of a solenoid with air, water, or aluminum doesn’t make much of a difference in the magnetic field created since the µ for these materials is approximately equal to µo. Wrapping the coils of wire that forms our solenoid around a pure iron rod, however, can multiplies the magnetic field by thousands. This is because the permeability of pure iron is thousands of times greater than that of empty space, air, water, and aluminum.

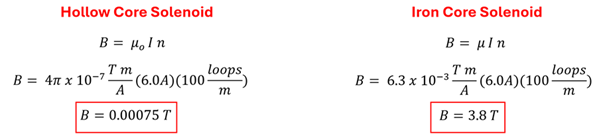

Example 3

Problem: In Example 2, we designed a hollow core solenoid with 100 loops/m and 6.0 A of current passing through it. We found the magnitude of its magnetic field to be 0.00075 T. Theoretically, what would the magnetic field be if we simply filled the core of that solenoid with pure iron?

Solution: We will still use our magnetic field equation for a solenoid, but we will replace µo with µ, the permeability of iron. Doing so yields a magnetic field thousands of times stronger!

In reality, the maximum magnetic field of an iron core solenoid is typically around 2 Tesla because of a phenomenon called magnetic saturation. For strong magnetic fields, most of the magnetic domains in the iron are already aligned. This prevents the field from continuing to increase with more current or a greater number of loops per length.

Nonetheless, what is so special about iron? What gives it a permeability value 5000 times that of a vacuum and many other materials? We learned back in Lesson 1 that a few elements—iron, nickel, and cobalt—are considered ferromagnetic materials. These are materials that can be permanently magnetized by an external magnetic that causes the alignment of magnetic domains. Other materials, such as air or aluminum, are paramagnetic materials. Paramagnetic materials interact weakly with an external magnetic field. In short, what makes iron so special is that the relatively weak magnetic field created by the solenoid itself aligns the domain within the iron making it into a very strong magnet.

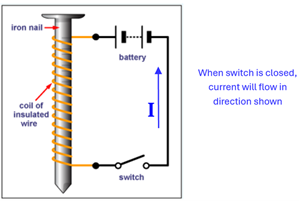

We have seen that an electromagnet is particularly useful for creating strong magnetic fields. There is another huge advantage to the electromagnet, however. Electromagnets can be turned on and off. Since the magnetic field is dependent on the current in the wire, simply opening a switch keeps current from flowing through the solenoid and thus no magnetic field is created. Closing the switch allows the current to flow creating the magnetic field.

What is interesting is that you can make a simple electromagnet with only a battery, wire, and an iron nail. If you ever try this, however, you need to do so safely. Since the wire offers very little resistance, connecting the wire directly to the two ends of a battery will produce a current flowing through the wire that is quite large. A large current will produce a great deal of heat. Take safety measures to not burn yourself if you ever try to create your own electromagnet.

Some of the strongest magnets in the world are electromagnets. You will find electromagnets used in a myriad of applications such as motors and generators, electric buzzers and headphones, junkyards cranes that pick up cars, and recycling plants that sort various types of metal cans. And that’s just the start! What is even better is that now you can understand how all these things work. Each of these contains a solenoid of wire wrapped around an iron core with current that can be adjusted to create the magnetic field desired. This makes the electromagnet one of the greatest inventions in the field of magnetism. The good news is there’s still much more to uncover in the lessons ahead.

Check your Understanding

Use the following questions to assess your understanding. Tap the Check Answer buttons when ready.

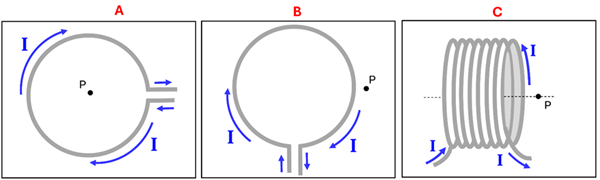

1. Determine the direction of the magnetic field at point P in each of these situations.

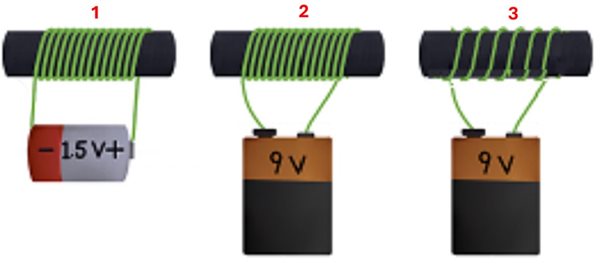

2. Recall from Ohm’s Law that I = V/R. Assuming each wire offers the same resistance ‘R’ and that each coil is wrapped around an identical ferromagnetic material. Rank the magnetic field produced by these three electromagnets from strongest to weakest.

Figure 3

3. A 0.30 m long solenoid is made of 32 loops. A current of 0.20 A flows through the wire in the direction shown. Determine the magnitude and direction of the magnetic field inside the solenoid when the core is (A) a vacuum, (B) filled with air, (C) filled with aluminum, and (D) filled with pure iron.

4. When the switch is closed, this nail will become an electromagnet. Which end of the nail—top or bottom—will become the north pole of this electromagnet? Explain how you know.

Figure 4

Figure 1 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Long-wire-right-hand-rule.svg

Figure 2 Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iron_nail_as_an_electromagnet.gif

Figure 3 Source: adapted from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Setup_-_electromagnet_1.png

Figure 4 Source: adapted from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iron_nail_as_an_electromagnet.gif