Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 1: Chemistry as a Lab Science

Part b: Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

Part 1a: Beyond the Scientific Method

Part 1b: Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

Part 1c: Experimental Design

Chemistry is a Verb

On the previous page of our lesson on Chemistry as a Lab Science, it was stated that Chemistry is a verb. Chemistry is something that you do. If it is a body of knowledge (a noun), then you can read about it. If it is a set of ideas (a noun), then you can think about it. If it is a collection of facts (a noun), then you can memorize it. The fact is that Chemistry is a body of knowledge, a set of ideas, and a collection of facts. But it is much more than that. Chemistry is a way of acquiring knowledge. Chemistry knowledge is discovered, acquired, and confirmed through lab work.

On the previous page of our lesson on Chemistry as a Lab Science, it was stated that Chemistry is a verb. Chemistry is something that you do. If it is a body of knowledge (a noun), then you can read about it. If it is a set of ideas (a noun), then you can think about it. If it is a collection of facts (a noun), then you can memorize it. The fact is that Chemistry is a body of knowledge, a set of ideas, and a collection of facts. But it is much more than that. Chemistry is a way of acquiring knowledge. Chemistry knowledge is discovered, acquired, and confirmed through lab work.

Chemistry is different than your other classes because the room is bigger. Think about your other classes. It is likely that back wall is located just behind the desks of the last row. The back wall of the Chemistry classroom is probably not located behind the last row of seats like it is in your other classes.  Unlike math class, history class, and English class, the back wall of the Chemistry classroom is located a good 30-60 feet behind the last row of desks. Lab tables and lab equipment, sinks and gas jets, goggle stations and fume hoods, fill this extra classroom space. The activity that happens in that space is what makes Chemistry class different than your other classes.

Unlike math class, history class, and English class, the back wall of the Chemistry classroom is located a good 30-60 feet behind the last row of desks. Lab tables and lab equipment, sinks and gas jets, goggle stations and fume hoods, fill this extra classroom space. The activity that happens in that space is what makes Chemistry class different than your other classes.

The room is bigger in Chemistry class because Chemistry is different than non-science subjects. Chemistry is unique. It is this extra 30-60 feet in the back of the room that makes it unique. In Chemistry class, the answers to our questions are found in the back of the room and not in the textbook. Every trip to the back of the room involves an effort to answer a question. The question must reign supreme in the mind of every student as they cross the threshold between where Chemistry is talked about as if it were a noun and where Chemistry is done. Chemistry as a verb happens in the back of the room.

Doing Chemistry Begins with a Question

The doing of Chemistry, the verb part, is like the doing of any other science. The doing of Chemistry begins with a question. Examples of questions that could fuel the doing of Chemistry in the back of the room include …

- What is the percent composition of salt, sand, and iron in a mixture?

- How do the properties of metals differ from that of nonmetals?

- Is mass conserved during a chemical reaction?

- What is the percent composition of the elements magnesium and oxygen in provided compound?

- How many Calories of energy are contained in a nut?

- How does varying the temperature affect the volume of a sample of gas?

- And many, many more.

A question must be a

testable question if it is to become the fuel for a Chemistry lab. That is, the question must be one for which a procedure could be designed in order to make observations and collect data capable of leading to an answer. For instance, if the question under study is

What is the percent composition of salt, sand, and iron in a mixture?, then there must be a procedure for separating salt, sand, and iron from one another when the three different types of stuff are present in a mixture. Once separated, there must be a means of measuring the amount of each type of stuff (for instance - the mass of sand, the mass of salt, and the mass of iron). If there are procedures for doing this, then we would say that this is a testable question.

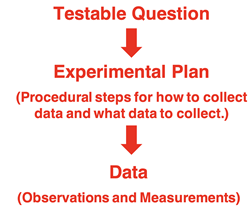

Experimental Procedures Yield Data

A testable question leads to an experimental plan for conducting the investigation. The goal of the plan is to

answer the question. This plan is sometimes referred to as a procedure. It includes details about what to do in order to collect data – observations and measurements – capable of answering the question. If the question is

What is the percent composition of salt, sand, and iron in a mixture?, then the procedure would describe steps for separating the salt and the sand and the iron from each other. It would also describe steps for making observations or measurements.

Documenting and Recording

Chemists are always careful to document and record their work. And as a Chemistry student, you will also need to learn how to document and record your lab work. This is often done in the form a lab report or a lab notebook entry. Your instructor will provide you specific directions as to what is required in the documentation for your class. Nearly all instructors require a section that includes a record of your observations and measurements. These are typically organized into a Data section. A sample Data section for the Salt-Sand-Iron lab is displayed below. Note how measurements are clearly labeled. A unit of measurement is indicated (more on this later). Calculations are shown and annotated. An

annotation is a short note clarifying how the calculation was carried out. Be sure to know your instructors expectations for documenting your lab work.

Claims Emerge From Data

Careful documentation of the data is critical when doing chemistry. Chemistry as a verb continues once the data is collected. It is inspected and analyzed in an effort to determine the answer to the testable question. The analysis may include additional calculations. It may include the construction of a graph or several graphs. But whatever the analysis involves, it is always directed towards the answering of the question. The answer to the question is referred to as a claim. If a lab begins with a testable question, then it ends with a claim (and a bit more … to be described later). The procedure and data collection and analysis are the pathway between question and claim.

Careful documentation of the data is critical when doing chemistry. Chemistry as a verb continues once the data is collected. It is inspected and analyzed in an effort to determine the answer to the testable question. The analysis may include additional calculations. It may include the construction of a graph or several graphs. But whatever the analysis involves, it is always directed towards the answering of the question. The answer to the question is referred to as a claim. If a lab begins with a testable question, then it ends with a claim (and a bit more … to be described later). The procedure and data collection and analysis are the pathway between question and claim.

Claims Require Support

As mentioned, the claim is an answer to the question. But it is not enough to just say what the answer is. It is important to provide support for your answer. You must identify the evidence that led to your answer and you must provide a logical explanation for why that evidence led to your answer and not another answer. We refer to this as evidence and reasoning.

The evidence and reasoning can be thought of as a logical argument. It’s the chance for the Chemistry student to present the case for why their claimed answer to the question is believable. It is the final opportunity for the student to express their understanding of the clear and logical line connecting the evidence (Data section) to the claim. The student explains, elaborates, argues, cites evidence, and makes their strongest appeal possible in favor of the claim. If a Chemistry lab were a courtroom trial, then the procedure, data collection, and analysis would be like the presentation of evidence by the witnesses. And the reasoning would be like the closing arguments in which the attorney attempts to use the evidence to persuade the jury or the judge of the claim that they are making.

The evidence and reasoning can be thought of as a logical argument. It’s the chance for the Chemistry student to present the case for why their claimed answer to the question is believable. It is the final opportunity for the student to express their understanding of the clear and logical line connecting the evidence (Data section) to the claim. The student explains, elaborates, argues, cites evidence, and makes their strongest appeal possible in favor of the claim. If a Chemistry lab were a courtroom trial, then the procedure, data collection, and analysis would be like the presentation of evidence by the witnesses. And the reasoning would be like the closing arguments in which the attorney attempts to use the evidence to persuade the jury or the judge of the claim that they are making.

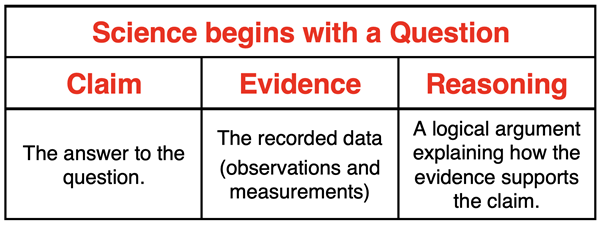

Claim-Evidence-Reasoning

A lab or experiment can be thought of as an effort to answer a question. The answer to the question is the Claim. The recorded data – observations and measurements – along with any accompanying calculations and graphs serve as the Evidence. The Reasoning is a collection of statements that attempt to show how the evidence logically leads to and supports the claim. The reasoning is filled with logical arguments that are intended to make the claim as believable as possible.