Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 1: In Search of the Atom

Part a: Democritus to Dalton

Part 1a: Democritus to Dalton

Part 1b: The Inside Story of the Atom

Part 1c: Subatomic Particles

From Indivisible to Divisible

We started Lesson 1 by discussing the effort of natural philosophers like Democritus and scientists like John Dalton to establish a reasonable belief in the atom as the indivisible building block of matter. Dalton was indeed successful in convincing the scientific world of the value and validity of thinking in terms of atoms. But the concept of the atom as indivisible was quickly dispelled by the work of J.J. Thomson (1899) and Ernest Rutherford (1911). The atom is not a solid, miniaturized billiard ball with no internal structure or contents. By 1911, it was well understood that the atom contained electrons and protons. And there was plenty of evidence suggesting that there may be a third particle contained in an atom.

We started Lesson 1 by discussing the effort of natural philosophers like Democritus and scientists like John Dalton to establish a reasonable belief in the atom as the indivisible building block of matter. Dalton was indeed successful in convincing the scientific world of the value and validity of thinking in terms of atoms. But the concept of the atom as indivisible was quickly dispelled by the work of J.J. Thomson (1899) and Ernest Rutherford (1911). The atom is not a solid, miniaturized billiard ball with no internal structure or contents. By 1911, it was well understood that the atom contained electrons and protons. And there was plenty of evidence suggesting that there may be a third particle contained in an atom.

The Neutron

The Neutron

In 1932, English physicist James Chadwick, a student of Ernest Rutherford, conducted studies of the element beryllium. When bombarding beryllium with alpha particles, Chadwick observed the emission of neutral particles. Chadwick confirmed that the particles had no charge and had a mass similar to the mass of a proton. Chadwick named these particles neutrons.

The Big Three

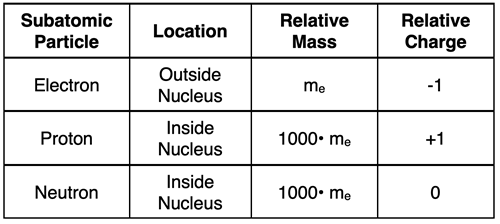

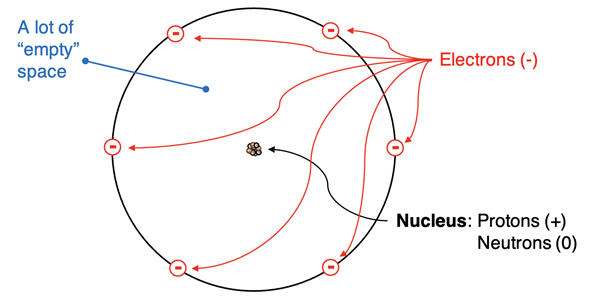

The proton, the neutron, and the electron are the three so-called subatomic particles. The proton and neutron are each approximately 1000 times more massive than the electron. And both are located in the nucleus. This means that nearly all the mass of an atom is located in its very dense center. The positive charge (possessed by protons) is in the nucleus and the negative charge (possessed by electrons) is outside the nucleus. For an electrically neutral atom, the number of electrons must equal the number of protons.

The Empty Space Model

The Rutherford atomic model and the Bohr atomic model are both considered nuclear models. That is, there is a dense, positively charged and massive nucleus at the core of the atom. The electrons are located outside the nucleus. And for both Rutherford and Bohr, those electrons can be thought of as being in orbit. The size of the nucleus is miniscule when compared to the size of the atom. Consider this comparison:

If the nucleus were the size of a golf ball, then the atom would be roughly the size of a professional sports stadium.

Put another way, the atom is about 100 000 times the size of its nucleus. When given these relative dimensions, one can imagine the atom as being primarily empty space.

The Rest of the Story

The story of the atom’s structure will continue in Chapter 5. For now, we need to learn the story of how the elements were organized into the Periodic Table. Continue to the Lesson 2 to learn the story of how a Russian chemist by the name of Dimitri Mendeleev organized the known elements into rows and columns.