Hold down the T key for 3 seconds to activate the audio accessibility mode, at which point you can click the K key to pause and resume audio. Useful for the Check Your Understanding and See Answers.

Lesson 2: The Periodic Table Revisited

Part a: Mendeleev and the Periodic Law

Part 2a: Mendeleev and the Periodic Law

Part 2b: Today's Periodic Table

Part 2c: Isotopes and Isotope Symbols

The Periodic of Periodic Table

The periodic table is perhaps the icon of Chemistry. Nearly every Chemistry classroom is adorned with a periodic table secured to at least one of its walls. When most people see a periodic table, they are seeing a table of elements. But the periodic table is more than that. It is

a table of patterns. Its oddly shaped organization has a rhyme and a reason to it. It is based on the belief that there are patterns of chemical and physical properties among the elements. Moving from element to element across a row of the table (known as a period), one observes that elemental properties change in a specific manner. The same pattern of change in those properties repeat themselves in each row. This is why it is called the

periodic table. There is a repeating pattern in the manner in which the properties of elements change.

Elements in the 1860s

In the 1860s, several chemists were working independently on a system of organization for the known elements. By the end of the 1860s, there were 63 known elements. The elemental symbols of the known elements are shown in the form of our current-day periodic table. The numbers indicate the relative mass of each element. The elements in the last column (Noble Gas group) had not yet been discovered. There were other

gaps where elements seemed to be missing. To truly appreciate the genius that will soon be described, it is important to remember that the above periodic table format had not yet been discovered.

In addition to the relative mass, chemists also knew values of a chemical property known as valence. Put simply, the

valence refers to the

combining power of an atom to form compounds with other elements. In the 1860s, the valence of an element was determined by the number of atoms of hydrogen that would combine with that element to form a compound. Aluminum formed the compound AlH

3 when combining with hydrogen. Its valence is 3. And calcium formed the compound CaH

2 when combining with hydrogen. Its valence is 2. The valence can also be determined from how many chlorine atoms or how many oxygen atoms would combine with the element to form a compound.

Consider an element with generic symbol

R, combining with the element hydrogen (H) or oxygen (O) to form compounds. The table shows how the valence is related to the formula of the compound that is formed.

The efforts in the 1860s to organize the elements into a table made use of what was known about the relative mass and the valence of the known elements.

The Periodic Law

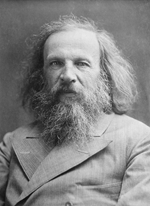

Dmitri Mendeleev, a 19

th century Russian chemist and professor, was writing a textbook for one of his classes. He was describing the chemical elements and how they could be classified according to similarities in their chemical properties. As the story is most often told, he wrote the names of the elements with their properties on note cards and laid them out in a row in order of their atomic mass. He noticed a pattern. It seemed that every seven elements, the same properties repeated themselves. For instance, the 2

nd element in the row (lithium) has near-identical properties as the 9

th element in the row (sodium). They both form compounds with oxygen having the general formula

R2O where

R is either Li or Na. And they both form compounds with hydrogen with the general formula

RH where

R is Li or Na.

Mendeleev also noticed that the 3

rd and the 10

th elements (Be and Mg) had similar properties. They form oxides with the formula

RO where

R is Be or Mg. And they both form compounds with hydrogen with the general formula

RH2 where

R is Li or Na. As a final example, Mendeleev observed that the 4

th and the 11

th elements (B and Al) had similar properties. They both formed compounds with oxygen having the general formula

R2O3 where

R is either B or Al.

Mendeleev continued to use the knowledge of relative mass and valence values to organize all the elements into families with similar chemical properties (i.e., valence). His organizing principle – the properties repeat themselves every 7 elements - became known as the

periodic law. Mendeleev would describe it like this:

When elements are arranged in order of increasing atomic mass, one observes a periodic repetition of their chemical and physical properties.

In 1869, Mendeleev organized 63 elements into a

periodic table. A revised version from 1871 is shown below.

Mendeleev’s Predictions

Mendeleev observed that there seemed to be some missing elements in his table. He assumed that these were elements that had not yet been discovered. For instance, he predicted that an element that had the same properties as aluminum and a relative mass between 65 and 70 would someday be discovered. In 1875, chemists discovered the element gallium. It had a relative mass of 70 and chemical properties similar to aluminum, matching Mendeleev’s prediction.

Mendeleev also predicted that an element with the properties of carbon and silicon would be discovered. He predicted its relative mass would be between 70 and 74. In 1886, chemists discovered the element germanium. It had chemical properties similar to carbon and silicon and had a relative mass of 72. Mendeleev also predicted the discovery of an element with the properties and relative mass of scandium; the element was discovered in 1879.

Paving the Way for the Modern Table

In

the next part of Lesson 2, we will trace period table history forward in time from Mendeleev’s work to the modern version. We will find that Mendeleev provided a great framework for thinking about how to organize the elements. His table from 1869 was constructed prior to the many advances in understanding of atomic structure.

The growing understanding of the atom in the first half of the 20th century solidified our understanding of how to organize the elements.